Behind the Sciences

Gray-blue work surfaces run along the walls at hip level, on them at irregular intervals stand cabinets with heavy metal doors and bright red digital displays, all kinds of high-tech equipment whose purpose is not immediately revealed, piles of Petri dishes, two old-fashioned Bunsen burners and – strangely, above the door hangs a squeaky green rod system with a shower head?Spy the germs

'This is an emergency shower. In case Ms. Peil goes up in flames, she can douse herself here,' Dr. Anke Gottfriedsen, who is responsible for quality control at Kryolan, humorously comments with a wink. In theory, this could happen, because microbiologist Peil works very close to those Bunsen burners. In practice, the scenario is highly unlikely, because the native Brandenburger is one thing above all: an absolute expert in terms of safety. As such, she has been responsible for hygienic control here in the company and controls 'S2,' the proprietary safety laboratory with legally strictly regulated standards, for 18 years. Only specially trained personnel may enter this space.

Free from...pathogenic Mircoorganisms

'Cosmetics regulation obligates us to produce in a way that the end user has no loss of quality or health problems such as allergies or inflammation of the skin,' explains Marlies Peil. 'Products should be as free as possible from micro-organisms; the legislature laid down limits for that.' Micro-organisms, which means mold, germs, yeast, can lurk everywhere: on machinery, tools, raw materials like base, powder particles, color enrichments, work clothing, on bulk ware, containers which will be filled, or on the insufficiently disinfected hands of employees.To ensure that everything is immaculate, there's a sampling scheme. It determines when and where periodical hygiene tests are performed; in addition to staff and equipment, the room air is also checked for contaminants with a special cleaner. 'We have to pay extra attention to products with a high water content,' explains the microbiologist, who is also a trained food engineer. 'Germs are particularly comfortable in water, and that's why this commodity is subject to the most painstaking controls.' It's not just the water itself that is constantly on the test bench. The pure-water unit, which guarantees pharmaceutical quality with its taps and pipes, also has a permanent place on the checklist, like everything else that gets wet. 'It's important that no puddles form in the bowls, and all hoses are properly hung up so that micro-organisms don't get any source of life in the first place,' says Marlies Peil, and then goes over to the order of the day: 'Today is hygiene control in the production area. We sweep with swabs, which look like giant cotton swabs, on the surfaces of machines, tables, and equipment and then secure every individual sample separately in a test tube.' Another test then checks whether everything has been properly cleaned and disinfected, to be sure that any microbes that may have been left behind are subsequently given everything they need to propagate. 'Ms. Peil does everything so that the little guys do very well,' reveals Dr. Anke Gottfriedsen. 'She gives them food and creates a cozy environment so they can multiply without restraint.'

Flowsheet

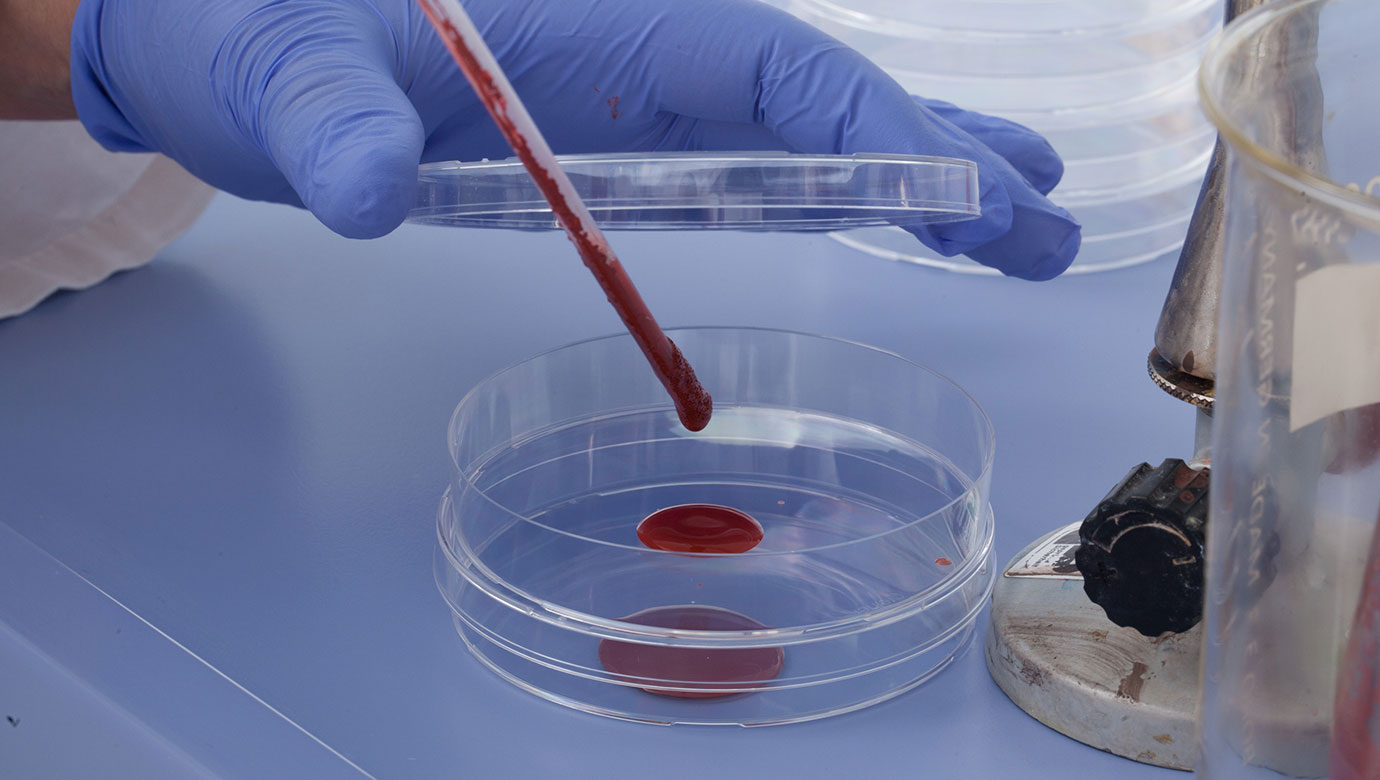

This tailor-made wellness program for single-celled organisms is quite sophisticated. For preparations, the initial equipment, like pipettes, flasks, and trays for sterilization, go into the 180 degree Celsius hot-air oven. During this procedure, the microbes' menu is prepared: nutrients, at an agreeable pH level between 4 and 8, e.g. a solution based on proteins (so-called buffered peptone water) to investigate raw materials that are not preserved. To test the purity of preserved products that prevent the boisterous growth of micro-organisms, the microbiologist resorts to a trick: 'We use an inactivation solution with a disinhibitor which incapacitates the preservative.' The next step is at the rich feast in the autoclave, a device that eliminates all impurities with a temperature of over 100 degrees Celsius and overpressure, ensuring that all components combine into a sterilized mass. To keep them liquid, their containers are subsequently temporarily stored in a 45 degree Celsius hot water bath. The Bunsen burner then comes into play: Ms. Peil pipets the sample of the microbe feast into the Petri dishes; to keep human germs from contaminating this mixture in this final step, she works so close to the sizzling flame that the layman is already hot just from looking at it. Once filled, the substrate is cooled down, becomes firm and is ready to absorb the swabs of various samples. The thus prepared Petri dishes then migrate into a fridge-sized thermocabinet, and their contents get time to incubate in the tropical environment of around 30 degrees Celsius. 'After three to five days, we have results. Germs show up relatively quickly; molds and yeasts grow somewhat more slowly,' according to Ms. Peil's experience.

Based on the spots on the glass, the expert can already recognize which family she's cultivated here. What exactly is behind it is revealed to her by a look under the microscope with an up to 80-times magnification.

And what happens if Kryolan's top hygiene specialist hits pay dirt in terms of micro-organisms? 'We check if the disinfection solution has the right concentration, and apart from that, contaminated tables, equipment, and samples get griped about. I talk to the employees and announce an instruction,' says Marlies Peil, and looks somewhat stricter through her fashionable glasses. 'Bulk ware that's not in order gets a quarantine label. We can say exactly which bulk is in which goods, so that we can weed it out specifically. Here, it doesn't matter how much weight we produce. We make the same tests for one kilo of bulk as for 100 kilos. Every assembled product only leaves the company if it has been tested and deemed to be pure.'

The Sherlockian nose

But even with meticulous work and the accumulated experience of 34 years of work, sometimes even the good Sherlockian nose of Marlies Peil gives up. 'We once had massive problems with a contaminated product, and invested a lot of energy and time to find out the cause,' she recalls. 'We'd accepted that it happened during the filling process,' her colleague Dr. Gottfriedsen adds, 'but could no longer track it in detail. Consequently, we've increased the percentage of parabens as a preservative up to the legal limit. They work like nothing else against all three - yeast, bacteria, and mold. In addition, they're less allergenic than other preservatives, and because they've been around for a long period and therefore are extremely reliable long-term studies. 'But why are preservatives necessary at all if the products still leave the production tables on Berlin's Papierstraße in an immaculate state? 'For one, because some germs only evolve naturally after months,' says Dr. Gottfriedsen. 'For another, dry products like powder are admittedly relatively safe because most microbes need water to live. But if you go in with a damp puff, you inadvertently supply them with their coveted food and they multiply.' That should and must be avoided in any case. And finally, the legislature requires cosmetic products to remain flawlessly pure for 30 months. 'If that's not provided, you have to apply a minimum durability date.Such as with our Ultra Underbase, a highly complex and sensitive product.'

While Marlies Peil explains, she checks if all current test results are documented in the computer and gathers together the Petri dishes collected in the system into a plastic bag. That bag then goes into the autoclave and, after just two hours at 134 degrees Celsius, the last micro-organism is nonviable.

The sudden potent smell is the reassuring sign: end of the single-cell party; closing time for the hygiene inspectors. With certainty, then, it will all continue smoothly tomorrow.